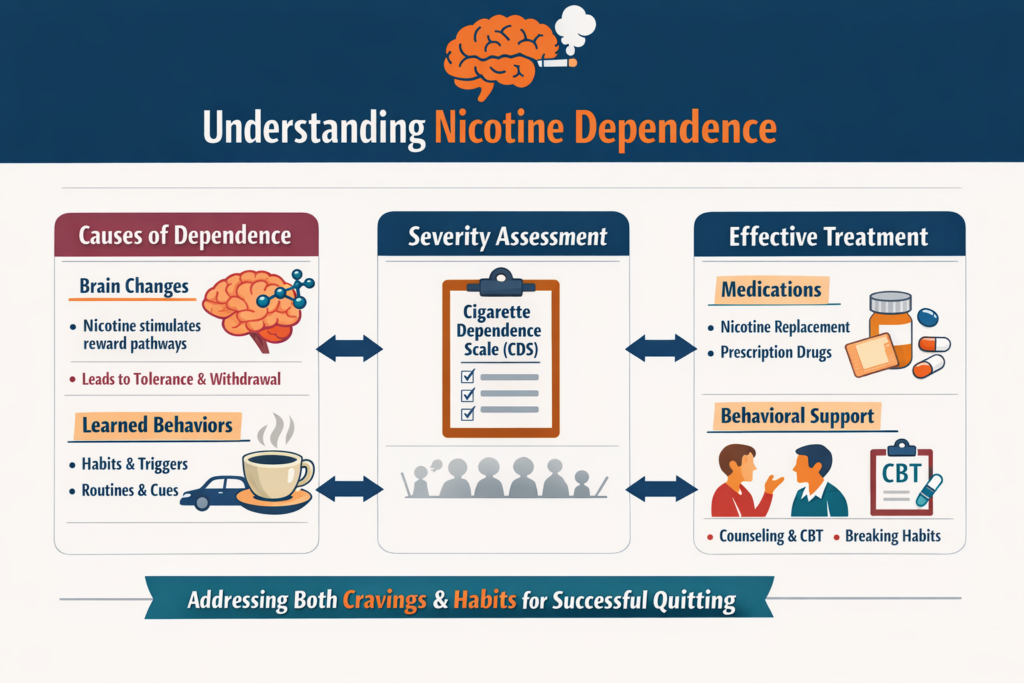

Nicotine addiction is a loss of control over tobacco use driven by both brain changes and learned behaviors. Nicotine stimulates brain reward pathways, causing craving, withdrawal, and compulsive smoking, while routines and triggers reinforce the habit. Dependence severity can be measured with tools like the Cigarette Dependence Scale. The most effective treatment combines medications (nicotine replacement or prescription drugs) with behavioral support to address both physical cravings and psychological habits.

Definition and Symptoms

At its core, nicotine dependence is a loss of control over nicotine or tobacco use, it is a state where the body and mind have adapted to the presence of nicotine, the primary addictive chemical in tobacco. When nicotine is withheld, a cluster of uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms emerges.

The symptoms of nicotine addiction can manifest in various ways, combining physical and psychological distress. Key indicators include:

- Loss of Control: Continuing to smoke despite the awareness of serious health issues, like lung or heart disease, caused by smoking, and despite the social consequences.

- Compulsive Use: Consumption despite the desire to quit. Repeated and unsuccessful attempts to quit or reduce tobacco consumption.

- Social Avoidance: Giving up activities or avoiding places where smoking is prohibited because of the inability to abstain.

- Withdrawal Symptoms: Experiencing symptoms upon cessation, such as intense cravings, irritability, anxiety, restlessness, difficulty concentrating, depressed mood, insomnia, increased hunger, weight gain and insomnia.

- Tolerance: The disappearance of side effects (e.g. nausea) experienced by new users, a reduced effect at a given dose, and the need to consume more to alleviate cravings and withdrawal symptoms. This is especially true for new smokers, because regular smokers usually smoke the same amount over many years.

- Early Morning Smoking: Lighting up a cigarette within the first 30 minutes of waking. The shorter the time to the first cigarette, the higher the degree of dependence.

Assessing the Degree of Dependence

While a clinical diagnosis of nicotine dependence is based on criteria established by psychiatric manuals, researchers and clinicians also employ self-report tests to measure its severity.

One such instrument, designed to provide a continuous and nuanced index of a smoker’s dependence, is the Cigarette Dependence Scale (CDS), developed by the author of this website and his colleagues. The shorter, 5-item version provides a quick test that can be used to tailor treatment. The longer, 12-item version (CDS-12) assessesmultiple facets of the dependence construct. By having the smoker rate statements on a five-point scale, the questionnaire provides a total score that clinicians can use to gauge the severity of the addiction, select the most appropriate treatment approach, and monitor the patient’s progress during cessation efforts.

The Biological Mechanism: Nicotine and the Brain

The invisible chain of addiction is forged in the brain’s complex circuitry. Nicotine acts as a powerful psychoactive agent, mimicking the natural neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

Upon inhalation, nicotine reaches the brain in mere seconds. There, it binds to specific protein channels, known as nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), located throughout the brain. When nicotine binds to these receptors, it triggers the release of several neurochemicals, most notably dopamine in the brain’s reward centers. This rush of dopamine produces the transient feelings of pleasure, focus, and reward that reinforce the act of smoking. The brain is somehow tricked to associate smoking with other rewards that are essential for survival.

With repeated exposure, the brain adapts: it produces an excess number of nAChRs in an attempt to compensate for the constant stimulation—a process called upregulation. This adaptation is the biological basis for tolerance, meaning the smoker needs more nicotine to achieve the same effect. When the nicotine supply is cut off, these upregulated receptors are left craving stimulation, leading to intense withdrawal symptoms and driving the compulsive need to smoke again. This cycle of seeking relief from discomfort is known as negative reinforcement, cementing the addiction.

The key factor is that the addictiveness of a nicotine delivery device depends on the speed at which nicotine is delivered to the blood and brain. Cigarettes have the fastest nicotine delivery, as a large amount of nicotine reaches the brain within seconds of inhaling a puff. In contrast, nicotine patches, gum, lozenges, and pouches deliver the nicotine dose much more slowly, so these products are not addictive. Electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products have a medium delivery rate, nd some of these products can also be addictive depending on the amount and speed of nicotine delivery.

The Behavioral Component: Triggers and Rituals

Cigarette addiction is not purely chemical; it is also deeply interwoven with learned behaviors and environmental cues. This is the behavioral component of the dependence.

Smokers repeatedly link the physical act of smoking with daily routines, emotional states, and social settings. The morning coffee, the work break, driving a car, finishing a meal, talking on the phone, or experiencing stress or anxiety all become powerful cues, or “triggers,” that signal the need for a cigarette. The mere sight or smell of tobacco, or being in the presence of other smokers, can elicit a powerful craving. These ritualistic associations create a psychological dependence that must be addressed alongside the physical addiction to ensure long-term cessation.

Treatment Methods

The treatment for cigarette addiction is most effective when it is multi-faceted, addressing both the biological craving and the deeply ingrained behavioral habits, and when it combines pharmacological with behavioral treatments.

Pharmacological Treatments aim to manage the physical symptoms of withdrawal and reduce the reinforcing effects of nicotine:30

- Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT): Available as patches, gum, lozenges, inhalers, and sprays, NRT delivers controlled doses of nicotine without the harmful toxins of tobacco smoke, and at a slower rate than cigarettes, making these products non-addictive. This helps mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Combining a long-acting form (like the patch) with a short-acting form (like the gum) for acute cravings is more effective than using either product alone.

- Prescription Medications: Drugs like varenicline, cytisine and bupropion are non-nicotine options. Varenicline and cytisine work by partially stimulating the nAChR, reducing both cravings and the pleasure derived from smoking, while bupropion, originally an antidepressant, is thought to influence dopamine and norepinephrine levels to alleviate withdrawal.

Although these are not medical treatments, you can also obtain nicotine from electronic cigarettes or nicotine pouches if you do not wish to use the medications mentioned above.

Behavioral Treatments focus on disrupting the psychological and learned components of the addiction:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): This approach helps the smoker identify their triggers and develop effective coping strategies and relapse prevention skills. It reframes the person’s thoughts and behaviors related to smoking.

- Counseling and Support: Individual or group counseling, often delivered by specialists or through telephone quitlines, provides essential support, motivation, and practical guidance on navigating the challenges of quitting.

- Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a specific technique used to help ambivalent smokers explore and resolve their feelings about cessation.

Successful smoking cessation is based on a combination of medication and behavioral support tailored to your individual needs and level of dependence. Millions of people have successfully quit smoking with the help of pharmacological and behavioral aids, and you can do it too, just like them, and improve your health immediately.

Use the ‘Comments’ field below to share your experience or to suggest imporovements to this article.

References:

Etter, JF., Le Houezec, J. & Perneger, T. A Self-Administered Questionnaire to Measure Dependence on Cigarettes: The Cigarette Dependence Scale. Neuropsychopharmacol 28, 359–370 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300030

Jean-François Etter, Comparing the validity of the Cigarette Dependence Scale and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Volume 95, Issues 1–2, 2008, Pages 152-159, ISSN 0376-8716, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.017.

Jean-François Etter, A comparison of the content-, construct- and predictive validity of the cigarette dependence scale and the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Volume 77, Issue 3, 2005, Pages 259-268, ISSN 0376-8716, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.015.

Leave a Reply