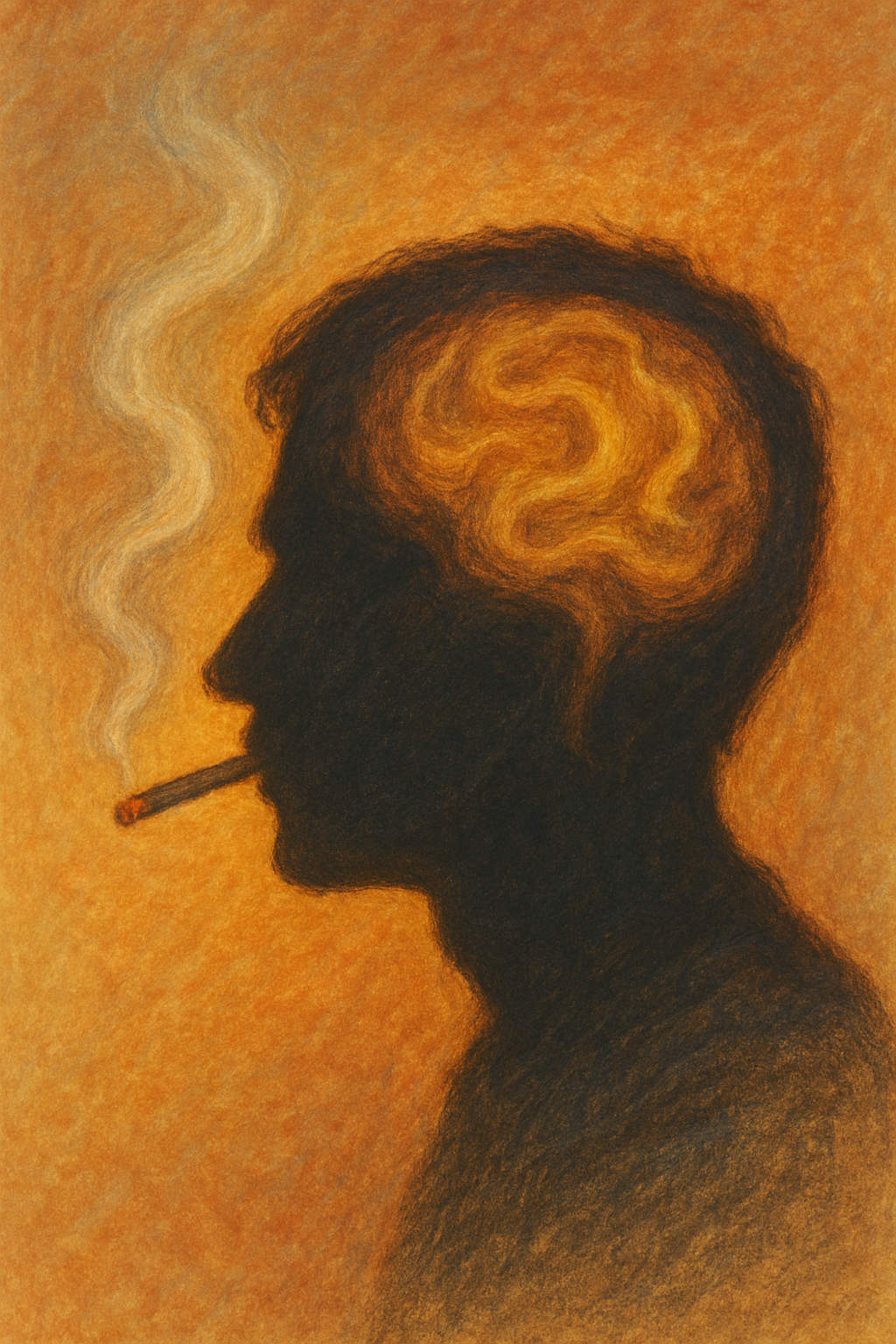

Smoking remains one of the main causes of ill health in people with mental disorders, yet it is still too often treated as a side issue in mental health care. While smoking rates in the general population have fallen steadily over recent decades, they remain stubbornly high among people with mental illness. This gap has become one of the main reasons why people with mental disorders die earlier than the rest of the population.

Across many countries, people with depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses are far more likely to smoke than those without these conditions. In psychiatric inpatient settings, smoking has historically been part of the culture, sometimes tolerated or even facilitated. As a result, tobacco use has become normalised in mental health services in a way that would now be unthinkable in most other areas of healthcare.

The consequences are profound. The excess deaths seen in people with serious mental illness are not primarily due to suicide or the psychiatric conditions themselves, but to heart disease, cancer and respiratory illness. Smoking is a major driver of all three. In effect, tobacco is responsible for a large proportion of the lost years of life experienced by people with mental disorders. Addressing smoking is therefore not a peripheral issue but central to improving both longevity and quality of life in this population.

One reason progress has been slow is the persistence of damaging myths. Perhaps the most enduring is the belief that people with mental illness cannot or do not want to quit smoking. This assumption has shaped clinical practice for decades and has led many healthcare professionals to avoid raising the issue altogether. Yet the evidence tells a very different story. Many people with mental disorders want to stop smoking, make repeated quit attempts and are just as motivated as other smokers. When offered appropriate support, they can and do quit successfully.

Another common fear is that stopping smoking will worsen psychiatric symptoms. This concern has been reinforced by the short-term irritability, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance that can accompany nicotine withdrawal. However, large studies and systematic reviews show that, once withdrawal has passed, people who stop smoking tend to experience improvements in mood, anxiety and overall wellbeing. These benefits are seen in people with and without diagnosed mental disorders.

Effective treatments for smoking cessation are available and work well for people with mental illness. Nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline have all been shown to increase quit rates in this group. For many patients with mental disorders, nicotine dependence is high, and standard doses of nicotine replacement are often insufficient. Combination treatment, using a nicotine patch to provide a steady background level together with faster-acting products (gum, lozenge, spray) for cravings, is frequently needed. Some highly dependent smokers require higher-dose or longer courses of nicotine replacement than those typically offered in primary care, and this can be done safely with appropriate clinical oversight.

What does require particular attention is the interaction between smoking and certain psychiatric medications. Tobacco smoke affects liver enzymes that break down drugs such as clozapine and olanzapine. When a patient stops smoking, blood levels of these medications can rise significantly, increasing the risk of side effects unless doses are adjusted. This is not a reason to discourage quitting, but it does mean that clinicians need to anticipate changes, monitor patients closely and modify doses where necessary. With planning and communication, these adjustments can be managed safely.

Changing outcomes for patients will also require a shift in professional attitudes. Too many mental health clinicians still see smoking as a lesser evil or as a coping mechanism that should be left untouched. Training is essential to build confidence in delivering smoking cessation support and in managing nicotine withdrawal and medication interactions. When smoking status is routinely assessed, discussed and treated as part of standard care, quit attempts become more frequent and more successful.

Service provision matters as well. People with mental disorders benefit from access to specialist smoking cessation services that understand the complexities of mental illness and can offer flexible, intensive support. Funding for these services is often inadequate, despite strong evidence that they are cost-effective and can dramatically reduce long-term healthcare costs. Integrating smoking cessation into mental health services, rather than referring patients elsewhere, increases engagement and reduces inequalities in access to care.

Smokefree policies in mental health facilities have an important role to play. When introduced thoughtfully, alongside ready access to nicotine replacement and staff support, these policies can reduce smoking without worsening mental health or increasing aggression. They also send a clear message that the physical health of people with mental illness matters just as much as their mental health.

Finally, there is a need for greater public and political awareness. Smoking among people with mental disorders has received far less attention than other health inequalities, despite its enormous impact. Policymakers, commissioners and service leaders need to recognise tobacco dependence as a treatable condition and a major driver of premature mortality in this population. Public discussion can help dismantle the stigma and low expectations that have allowed this problem to persist.

Reducing smoking among people with mental illness is one of the most effective ways to improve both mental and physical health outcomes. The tools already exist. What is required now is the will to use them consistently, compassionately and at scale.

Use the Comments field below to share your experience or to suggest improvements to this article.