What’s Really Inside a Cigarette

When someone lights a cigarette, they are consuming far more than just dried tobacco. They are engaging with a highly sophisticated, meticulously engineered chemical delivery system designed to maximize addiction and appeal. Understanding the components that make up a cigarette—from the tobacco blend itself to the paper, the additives, and the filter—reveals a product whose design prioritizes biological efficacy over consumer safety.

The Tobacco Blend: Types and Treatment

A typical cigarette relies on a mixture of different tobacco types, blended to achieve a specific flavor profile and, crucially, to optimize nicotine delivery.1 The primary tobaccos used are:

- Flue-Cured (Virginia) Tobacco: Often high in natural sugars, this tobacco is cured in heated barns, resulting in a milder, slightly sweeter flavor.2

- Burley Tobacco: Air-cured, this tobacco is low in sugar but highly porous. This porosity allows it to readily absorb the various additives and flavorings manufacturers introduce.

- Oriental Tobacco: Sun-cured, this tobacco offers a highly aromatic and strong flavor, often used in smaller quantities for seasoning the blend.3

Modern manufacturing often employs processes like “reconstituted tobacco” (made from scraps and stems) and “expanded tobacco” (puffed up using gases) to reduce costs and control the filling properties of the cigarette.4 The real chemical intervention, however, occurs through the use of ammonia compounds. These compounds increase the alkalinity (pH) of the smoke, which converts the nicotine within the tobacco into its “freebase” form. This freebase nicotine is vaporized more easily, allowing it to be absorbed rapidly by the lungs, delivering a potent and immediate hit to the brain—a key mechanism that enhances the addictive power of the product.

Additives: The Secret Ingredients

Manufacturers incorporate hundreds of different chemical additives, often claiming they enhance flavor or act as humectants to keep the tobacco moist.5 Yet, many additives serve a more sinister purpose: making the smoke easier to inhale and increasing the bioavailability of nicotine.

Common additives include:

- Sugars and Humectants (e.g., glycerol and propylene glycol): These are added to maintain moisture, but when they burn, they create toxic compounds, including acetaldehyde.6 Acetaldehyde is not only a probable carcinogen but may also enhance nicotine’s addictive properties in the brain.7

- Bronchodilators: Certain additives, like cocoa, act as bronchodilators, slightly relaxing the airways.8 This allows the smoker to inhale the toxic smoke deeper into the lungs, increasing the amount of surface area available for nicotine absorption.

- Flavorings (e.g., menthol): Menthol has a cooling, anesthetic effect that masks the harshness and irritation of the smoke, making it easier for new smokers to start and deeper inhalation more comfortable for long-term smokers.9 This makes menthol cigarettes highly addictive and difficult to quit.

Nicotine Dosage Control: A Pharmacological Precision

The tobacco industry’s control over nicotine dosage rivals the precision used by pharmaceutical manufacturers. They don’t simply rely on the natural nicotine content of the tobacco leaf; they manage the entire system to ensure the smoker receives a consistent, addictive dose. This control is achieved through the use of ammonia and the deliberate engineering of the cigarette’s physical structure.

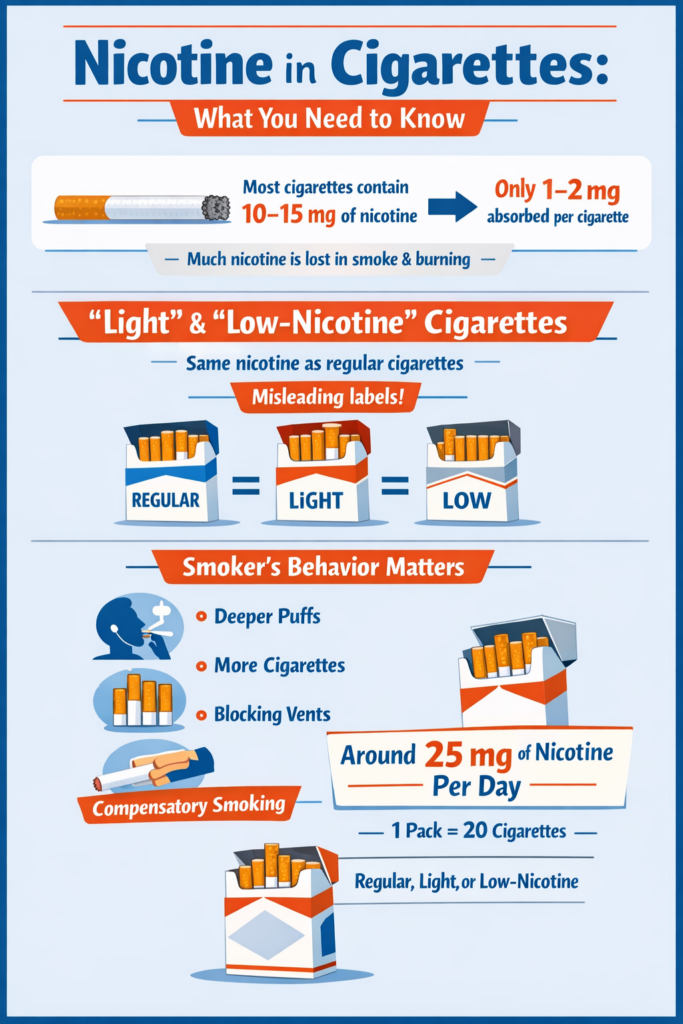

By managing the levels of freebase nicotine and controlling the burn rate, the manufacturers effectively dictate how much nicotine the smoker receives per puff. This level is finely tuned to maintain addiction without immediately overwhelming the user, ensuring long-term product use. They adjust the blend and engineering to create cigarettes with different labeled strengths, but even “light” or “low-tar” versions often deliver the same amount of actual nicotine, as smokers simply inhale deeper or more frequently to reach their desired nicotine level.

The Role of Paper and Combustion Regulation

The paper wrapped around the tobacco is far from a neutral wrapper; it is an active component in regulating combustion and toxin production.10 Cigarette paper is often treated with chemicals like potassium nitrate to control the burn rate. This allows the cigarette to burn evenly and remain lit, even when not actively puffed, preventing the frustration that might lead a user to extinguish it prematurely. This controlled burn affects the temperature of the smoke, which in turn influences the formation of toxins and the release of nicotine.

Ventilation Holes: The Deception of “Light” Cigarettes

In the 1970s and 80s, manufacturers introduced ventilation holes—tiny laser-perforated holes found in the filter paper near the tip. This modification was the core feature of cigarettes marketed as “light” or “low-tar.”

When the cigarette is placed in a smoking machine for measurement, these holes allow outside air to mix with the smoke, effectively diluting the measured tar and nicotine yield, resulting in the lower numbers printed on the packaging. However, when a human smokes, they invariably block these ventilation holes with their fingers or lips, or they simply inhale deeper and faster to compensate for the dilution.11 The net result is that the smoker receives essentially the same, or even a higher, dose of tar and nicotine than they would from a regular cigarette, rendering the “light” designation meaningless in real-world use.

The Filter: A False Sense of Security

The cigarette filter, typically made of cellulose acetate—a form of plastic—is widely misunderstood by the public.12 While it does trap some particles of smoke, its primary function is psychological and physical, not protective.

The filter cools the smoke and provides a firmer structure for the smoker to hold, preventing loose tobacco from entering the mouth. While it captures larger particulate matter, it does virtually nothing to filter out the most dangerous components: the toxic gases (like carbon monoxide) and the vast majority of the microscopic, deeply penetrating fine particles that carry carcinogens into the lungs. The filter provides a potent, yet false, sense of security to the smoker.

The Environmental Aftermath: Cigarette Butts

Once a cigarette is finished, the filter becomes a major environmental pollutant.13 Cigarette butts are the most frequently littered item in the world, with trillions discarded annually.14 Because they are made of plastic (cellulose acetate), they do not biodegrade rapidly; they simply break down into smaller and smaller pieces of plastic, known as microplastics.

These littered butts leach toxic chemicals—including nicotine, heavy metals, and various combustion byproducts—into soil and water, harming marine life and contaminating the environment.15 A single cigarette butt can be toxic enough to kill small fish in a liter of water.16 The pollution caused by these discarded plastic filters represents the final, lingering chemical cost of tobacco use.