What is COPD?

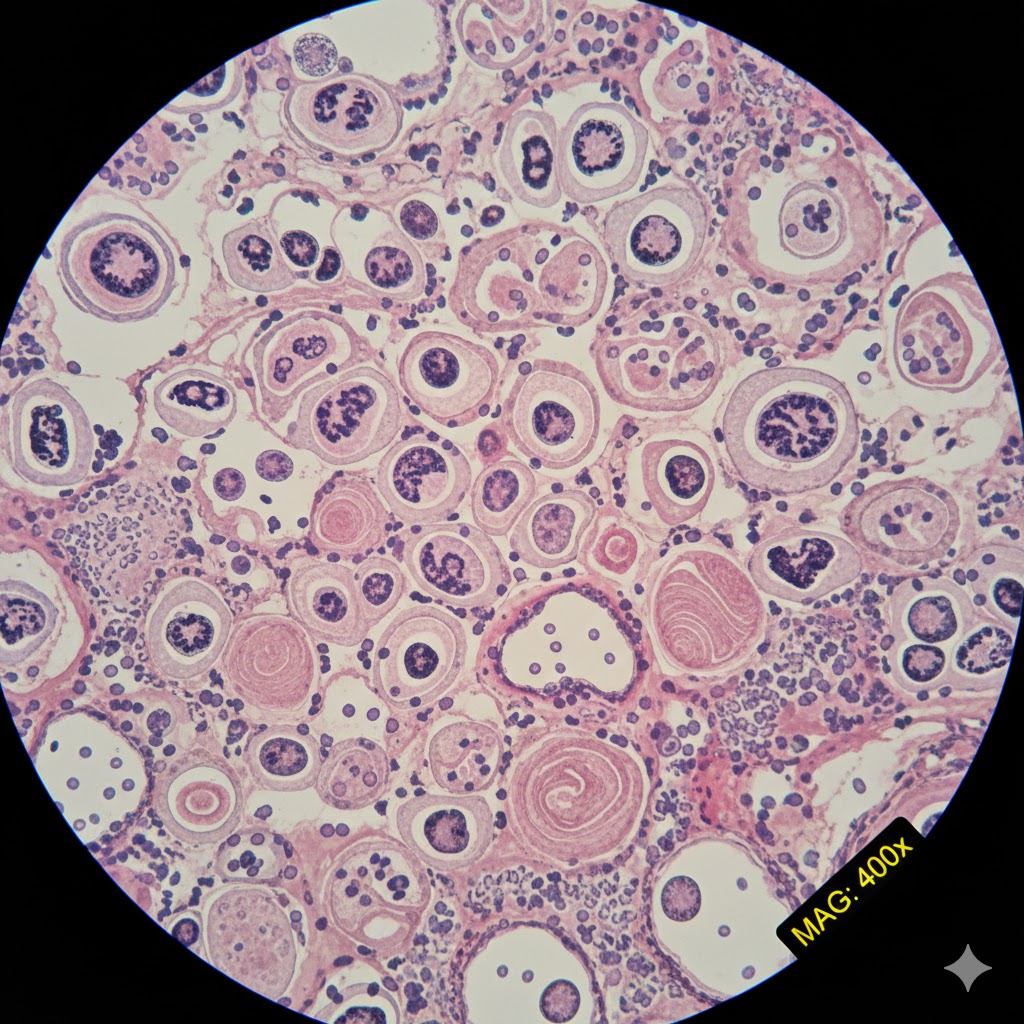

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, universally known by its acronym COPD, is a serious, progressive lung disease that significantly impedes airflow to and from the lungs, making breathing increasingly difficult. It is not a single disease, but an umbrella term that mainly encompasses two conditions: emphysema and chronic bronchitis. In emphysema, the delicate walls of the air sacs (alveoli) are damaged, losing their elasticity and creating larger, less efficient air spaces. This destruction reduces the surface area available for oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange and causes old, stale air to become trapped in the lungs. Chronic bronchitis, conversely, involves long-term inflammation and irritation of the airways (bronchial tubes), leading to increased mucus production and a persistent, phlegm-producing cough. Both components contribute to the defining characteristic of COPD: airflow obstruction.

Prevalence Across Populations

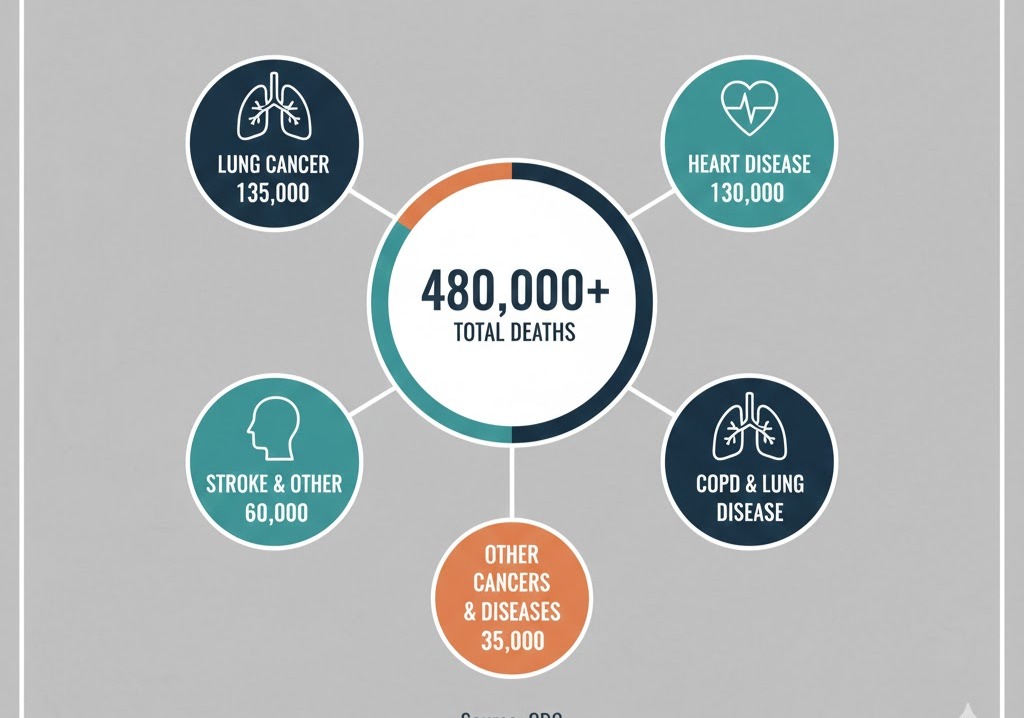

COPD is a major global health concern and one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide. The risk of developing this condition rises significantly with age. While symptoms are uncommon in people under 40, prevalence escalates rapidly thereafter, often affecting middle-aged and older adults. The highest rates are seen in individuals aged 60 and over, with one study showing the prevalence jumping from around 5% in those under 50 to over 21% in those 60 and older.

The most powerful predictor of COPD is smoking status. Current and former smokers bear the heaviest burden of the disease. Current smokers have a prevalence rate dramatically higher than that of never-smokers—in some populations, this difference can be two- to threefold. Ex-smokers, while at a lower risk than current smokers, still face a significantly elevated risk compared to those who have never smoked, underscoring the long-term damage caused by smoking. Crucially, as many as one in four individuals diagnosed with COPD have never smoked, revealing that while smoking is the main culprit, it is not the only one. Recent data also shows that in many high-income countries, the prevalence of COPD is increasing among women, a trend linked to the rise in female smoking rates over the past several decades.

Causes, Risk Factors, and Disease Progression

The primary cause of COPD in developed countries is long-term exposure to tobacco smoke, which accounts for approximately 80% to 90% of cases. The harmful chemicals in cigarettes, pipes, cigars, and marijuana smoke injure the lining of the lungs and airways, triggering the inflammation and damage characteristic of the disease. The longer a person smokes, the greater the risk. Even exposure to secondhand smoke can increase risk.

Beyond smoking, other important risk factors include:

- Occupational Exposure: Long-term inhalation of dusts (such as coal, grain, or silica), chemical fumes, and vapors in the workplace can damage the lungs.

- Air Pollution: Chronic exposure to high levels of indoor air pollution (particularly from burning biomass fuels like wood or dung for cooking and heating in poorly ventilated homes) and outdoor air pollution contributes to risk, especially in the developing world.

- Genetics: A rare genetic condition called alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency makes a small percentage of people highly susceptible to lung damage and COPD, often at a younger age. Other, more common genetic factors may also make some individuals more vulnerable to the damaging effects of smoke and pollutants.

- Asthma: Having asthma, particularly if combined with smoking, is an additional risk factor.19

COPD is a slowly progressive disease.20 Early on, symptoms may be subtle—a persistent cough often dismissed as a “smoker’s cough,” or slight shortness of breath during physical exertion.21 Over many years, as the lung damage accumulates, symptoms worsen.22 Shortness of breath becomes more pronounced, limiting daily activities, and flare-ups, known as exacerbations, become more frequent and severe.23 These exacerbations, often triggered by respiratory infections, lead to a more rapid decline in lung function and are a major predictor of poor outcomes.24

Consequences of Untreated Disease

Ignoring the symptoms and leaving COPD untreated has severe consequences.25 Without intervention, the accelerated decline in lung function continues, leading to increasing disability, reduced quality of life, and eventual premature death.

The damage is not confined to the lungs. COPD causes chronic low-grade inflammation throughout the body, which is strongly linked to the development and worsening of other serious health issues, known as comorbidities.26 These include:

- Cardiovascular Disease: Patients with COPD have a significantly higher risk of heart attack, stroke, and heart failure, sometimes even independent of their smoking history.27

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Cor Pulmonale: Damage to the lungs can increase pressure in the arteries that carry blood from the heart to the lungs (pulmonary hypertension), which strains the right side of the heart and can lead to right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale).28

- Respiratory Infections: Untreated individuals are highly susceptible to recurrent, severe respiratory infections like pneumonia, which often trigger dangerous exacerbations.29

- Frailty, Weight Loss, and Muscle Wasting: Severe shortness of breath can make eating and moving difficult, leading to malnutrition, weight loss, and reduced muscle mass.30

- Depression and Anxiety: The physical limitations and chronic nature of the illness often lead to psychological distress.31

Treatment Options, Effectiveness, and Side Effects

While the lung damage caused by COPD is permanent and cannot be reversed, treatment can significantly slow the disease’s progression, manage symptoms, and improve quality of life.32

Medication is a cornerstone of treatment.33 Inhaled bronchodilators (both short-acting for quick relief and long-acting for daily control) work by relaxing the muscles around the airways to open them up and make breathing easier.34 In more severe cases or for patients prone to exacerbations, inhalers combining bronchodilators with inhaled corticosteroids (anti-inflammatory drugs) are often used.35

- Effectiveness and Side Effects of Inhaled Therapy: Inhalers are highly effective in managing daily symptoms and reducing the frequency of flare-ups. Short-acting bronchodilators may cause temporary side effects like a fast heart rate or tremor. Inhaled corticosteroids, while generally well-tolerated, carry a small risk of oral thrush (a mouth infection) and hoarseness.36

- Oral Steroids and Other Medicines: For severe exacerbations, short courses of oral corticosteroids are prescribed but are avoided for long-term use due to serious side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, and increased risk of infection.37 Other medicines, such as the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor roflumilast, can be used by specialists to reduce airway inflammation and prevent flare-ups in certain high-risk patients, though they can cause gastrointestinal side effects.38

Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) is arguably the single most effective non-pharmacological treatment. It is a comprehensive program that includes tailored exercise training, disease education, nutritional counseling, and psychological support.39 PR significantly improves exercise capacity, reduces symptoms of breathlessness, enhances quality of life, and decreases hospital readmissions.40

Oxygen Therapy is prescribed for patients with advanced COPD who have severely low oxygen levels in their blood (hypoxemia).41 Long-term oxygen use can extend life and improve heart function.42

In a very small number of carefully selected patients with very severe, localized emphysema, surgical interventions like lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplant may be considered.43

Prevention Strategies

Prevention is organized into three levels, all of which are vital for controlling the burden of COPD.

Primary Prevention (Preventing the Disease)

The most critical primary prevention measure is smoking cessation.44 Since tobacco smoke is the overwhelmingly dominant cause, strategies must focus on discouraging young people from starting and providing effective support and resources to help current smokers quit.45 Combining counseling with cessation medications or nicotine replacement therapy can double or triple a person’s chances of successfully quitting for good.46 Eliminating or reducing exposure to other known risk factors, such as advocating for and enforcing clean air policies to mitigate occupational dust and fume exposure, is also essential.47

Secondary Prevention (Early Detection and Intervention)

Secondary prevention aims to catch the disease early, before significant, debilitating lung function loss occurs, and to stop its progression.48 The single most important secondary prevention measure is encouraging all smokers and ex-smokers with respiratory symptoms (even a “mild” cough or breathlessness) to undergo spirometry, a simple breathing test used to diagnose COPD. Early diagnosis allows for prompt intervention—especially immediate smoking cessation—which is the only intervention proven to alter the natural course of the disease and slow the decline in lung function.49

Tertiary Prevention (Preventing Complications)

For individuals already diagnosed with COPD, tertiary prevention focuses on managing the disease to prevent acute exacerbations and debilitating long-term complications.50 Key measures include:

- Vaccinations: Patients should receive annual flu and pneumonia vaccines, as well as the COVID-19 and RSV vaccines as recommended, to prevent infections that can trigger severe flare-ups.51

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation: As discussed, PR is a powerful tool for preventing deconditioning and managing symptoms.52

- Effective Medication Use: Strict adherence to prescribed inhaled maintenance therapy helps keep airways open and reduces the risk of exacerbations.

- Comorbidity Management: Aggressively treating coexisting conditions like heart disease, osteoporosis, and depression improves overall outcomes and quality of life.

Use the Comments field below to share your experience with COPD or to suggest imporovements to this article .